The below article featured on the BrexitCentral website on 16th September 2019.

The Liberal Democrats have devoted a great deal of time at their party conference to attacking my predecessor as Witney MP, David Cameron, over his decision to call the EU referendum. These attacks are an attempt to sanitise their own role in campaigning for – and to airbrush their contribution to securing – that very referendum.

Let’s get some of the basics clear first. The Conservative manifesto promise to hold an in/out referendum was endorsed by the British people in 2015, being crucial to the party’s majority at that year’s general election. The very fact that the British public voted to Leave a year later demonstrates how wide and deep was discontent in Britain at the country’s EU membership, at least without fundamental reform. Ever since the advent of the euro, and the further integration required to sustain it, Britain and the EU were on different paths requiring at the very least a fundamentally reformed relationship. Cameron is correct that a referendum was, at some point, probably inevitable in any event.

We should not forget: the referendum was not called by Cameron alone. Even as Prime Minister, he did not have the authority to simply call the referendum. That required an Act of Parliament, which passed by an overwhelming majority with 544 MPs in favour and just 53 against at Second Reading. As it happened, seven of the Lib Dems’ then eight MPs voted for the EU Referendum Bill in 2015.

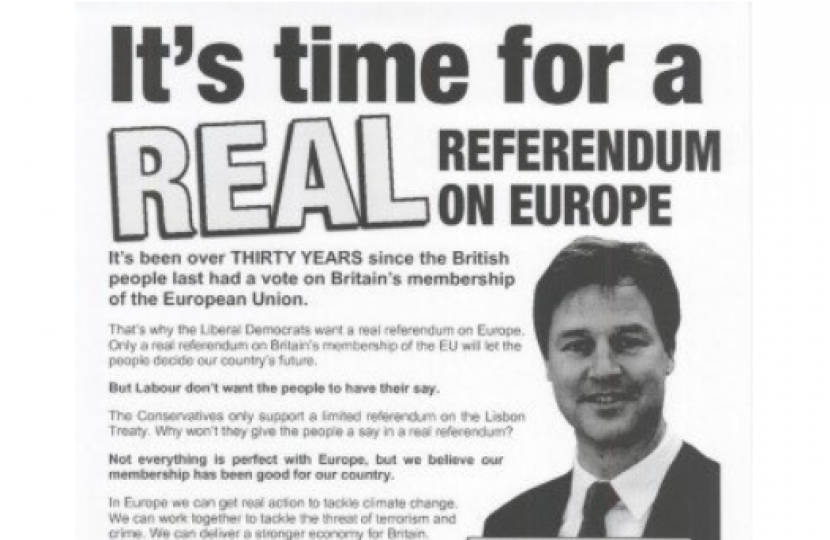

But the Lib Dems’ hypocrisy does not end there. For all the vitriol they pour on Cameron for holding the referendum, the Lib Dems neglect to mention that they were calling for an in/out referendum on the EU many years before the Conservative Party. Indeed, we have all seen the infamous 2008 Lib Dem campaign leaflet circulating on Twitter – very familiar to those of us who were Conservative activists at the time – featuring a fresh-faced Nick Clegg demanding “a real referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union.” The leaflet observed that:

“It’s been over thirty years since the British people last had a vote on Britain’s membership of the European Union. That’s why the Liberal Democrats want a real referendum on Europe. Only a real referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU will let the people decide our country’s future.”

2008 was also the year that Clegg infamously stormed out of the House of Commons when the then speaker, Michael Martin, refused to call a Lib Dem amendment in his name demanding an in/out EU referendum.

Following Ed Davey’s expulsion from the chamber, Clegg said:

“I share the dismay of [Ed Davey]. What guidance can [the Deputy Speaker] give me on how we can secure – if not today, at some point during the remaining stages of the Bill – the opportunity to debate the issue that many members want debated and many members of the public want debated: our future membership of the EU?”

Davey (then the Lib Dems’ foreign affairs spokesman) had struck an even more forceful tone, remarking:

“Will the Chair reconsider the decision not to select the Liberal Democrat amendment for a referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU? That is the question that goes to the heart of the debate before the House. That is the debate that people want to hear. We are being gagged, Sir.”

The current Lib Dem Leader, Jo Swinson, also contributed to this debate, and her speech is fascinating when compared with the comments she made at the weekend. Swinson repeated that:

“The Liberal Democrats would like to have a referendum on the major issue of whether we are in or out of Europe.”

On an in/out EU referendum, she noted:

“We support such a referendum; we will continue to campaign for it and hope that it will find favour in this House.”

Furthermore, she described being denied a vote on Clegg’s referendum amendment as “incredibly disappointing” and something she felt “very passionately” about.

Swinson’s eurosceptic side – mysteriously neglected of late – was also on display, as she noted:

“For too long, power in the EU has been concentrated among those who are appointed, not elected. The structures of the EU have often proved cumbersome to say the least, at times even making this House look modern and streamlined by comparison.”

The Lib Dems remained proponents of an in/out referendum at the 2010 General Election which saw them enter into a Coalition Government with the Conservatives, with a carefully caveated manifesto promise to hold a referendum “the next time a British government signs up for fundamental change in the relationship between the UK and the EU”.

The fact that the Lib Dems long advocated giving the British people a say on our membership of the EU, and indeed were the first mainstream party to call for an in/out referendum on the matter, makes their new pledge to cancel Brexit without even a second referendum all the more extraordinary. And that, itself, being an evolution from a position that a second referendum result would only be respected if it resulted in a Remain vote.

Seemingly without a hint of self-awareness, Lib Dem party policy is now to ignore the result of a referendum for which they themselves were the first to call. This wildly divisive policy shows the Lib Dems to be utterly disinterested in bringing the country together, their uncompromising approach only serving to fuel further discord and division. There is nothing inherently wrong with regretting a referendum result, but it is deluded to think that pretending it didn’t happen is going to lead to anything other than bitter polarisation.

It is therefore no surprise that Lib Dem grandee Sir Norman Lamb has warned that the party is “playing with fire”, describing the new policy as “a threat to the social contract” that risks dividing an already fractured country further.

Let’s be clear: nullifying a referendum for which the Lib Dems were the first to call, which was overwhelmingly endorsed by Parliament and which was the largest democratic exercise in our nation’s history, is not a moderate position. Neither liberal, nor democrats, this party has become the truly extremist force in British politics.

Robert Courts MP