UPDATE: I produced the below analysis over the course of the weekend as I prepared to speak in today’s debate on the Withdrawal Agreement, ahead of tomorrow’s vote. However, earlier today, the Government took the decision to delay tomorrow’s vote and therefore cancel the debate in which I intended to speak.

Whilst I will wait to see what “assurances” the Prime Minister is able to secure from EU leaders in her forthcoming talks, I think it appropriate to publish my full analysis of the Withdrawal Agreement as it currently stands, so that constituents are aware of my position.

I will update everyone further as soon as the Withdrawal Agreement is once again brought before Parliament.

-

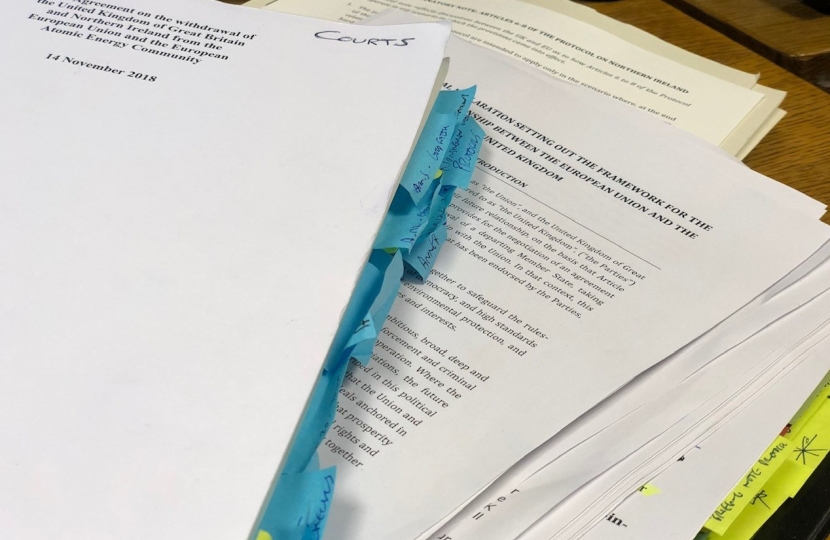

I have thought long and hard about every issue raised by the Withdrawal Agreement, including reading and re-reading it multiple times, speaking to Ministers at the highest level, experts of all points of view, and reading numerous pages of commentary. I have also spoken to countless constituents about the Agreement, and listened to all the debates in Westminster.

Throughout these many hours of work, I have resisted making any final statement until I was confident that I had understood the issues and what they meant for our area, and our country.

Before I go on, some points need restating at the outset.

Firstly, whatever view I come to, and however I vote, I will disappoint a significant percentage of people. I cannot please you all, but what I can do is to explain to you all, in detail, my reasons for proposing to vote as I do.

Secondly, it cannot be repeated often enough that whether anybody approves or disapproves of the “deal” that has been negotiated should have nothing to do with whether they voted Leave or Remain. For example, Leavers have been joined by committed Remainers, from all sides of the House, such as Jo Johnson, Damian Collins, Dominic Grieve and, recently, Sam Gyimah, in criticising the approach taken - or even refusing to support it. Equally, there are Leavers, like Michael Gove, Andrea Leadsom and Liam Fox, who do support it.

Thirdly, this is not about whether leaving with or without a “deal” is desirable - personally, I have always been clear that I want one - but whether this deal is one that establishes an acceptable future for our country.

This decision is about the way in which the UK will be governed in future, and the democratic accountability that will exist between the public and those who make the laws that we all live under.

I want to see a Britain that is open, liberal, modern, outward-looking. A Britain that seizes the opportunity of Brexit as a moment of national renewal; a chance to build a more democratic nation where power is more accountable, devolved downwards and inspires communities and individuals to take greater control of their lives. As cynicism for liberal democracy grows around Europe, Brexit gives Britain a unique chance to revitalise our proud democratic traditions and restore the vital link between the governed and the government.

Contrary to many people’s anxieties, Brexit is not about ‘turning our back on Europe’, but rather about building a new relationship with the European Union that sees us transition from noisy lodgers into friendly neighbours.

The truth is that the UK has never been – and never will be – comfortable with the political aspects of the European Union and its integrationist ambitions. Better surely to build a new relationship with our European allies around the things we do like – the free trade and close co-operation – than wrestle from within the project, feebly trying to hold back the unpalatable tide of ‘ever closer union’, which hardly anyone in the United Kingdom has ever wanted.

My task is to consider whether or not this Withdrawal Agreement is likely to deliver on this vision. Does it restore the UK’s sovereignty and democratic accountability? Does it withdraw us from the political, integrationist instincts of the European Union and the European Court of Justice? Does it set us on a path towards a new, amicable relationship with the EU built around free trade and friendly co-operation? Does it enable us to thrive as an independent nation state, free to forge new ties and reinvigorate old ones with nations around the world? And crucially, does the Withdrawal Agreement provide for a sustainable, lasting new relationship with the EU that enhances – not undermines – our democratic institutions and preserves our precious United Kingdom?

To do so, I have gone through the Withdrawal Agreement in detail. I have attempted to explain, clearly and simply, what is contained in these mammoth documents, and what they mean to us all. I have referred to some of the relevant Articles at important points, so you can go and read them for yourselves if you wish, but have tried not to let this become a lawyer’s essay. Nonetheless it is rather lengthy, and I hope that you will forgive me for that. But then, this is complicated stuff.

I shall explain these issues below, as follows:

- What the Withdrawal Agreement contains;

- What the Withdrawal Agreement actually means for the period of the Transition Period, both positive and negative;

- The two ways of moving from the Transition Period to the Future Relationship:

a.) A future trade agreement, what it means and whether we are likely to get there;

b.) The Backstop if we failed to agree a Future Relationship, what it means, whether we are likely to get out of it, and the alternative of extending the Transition Period;

- Other considerations;

What the Withdrawal Agreement contains

Before we look at whether we should welcome or reject the Withdrawal Agreement, let us take a cool, calm look at what it contains.

There are in fact two documents:

the Draft Withdrawal Agreement, which is some 599 pages long, and is legally binding as a treaty;

the 26 page Political Declaration on the Future Relationship, which is not legally binding and is a rather vague, aspirational document dealing with where the UK and EU may go in the future;

The Withdrawal Agreement contains three important concepts. The first of these is the Transition Period. This is a two-year period, starting at 11pm on the 29th March 2019 when the UK is to leave the EU, as enshrined in the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018. During this two-year period, the UK will obey all the rules of EU membership but without any representation. This is to be followed by one of two things: either the Future Relationship, which is where we are meant to be heading and which is described in the Political Declaration, or the Northern Ireland protocols, known as the “Backstop”, which are to come into effect if the EU and the UK cannot agree on the Future Relationship.

What the Withdrawal Agreement actually contains - the positives

There is certainly much to welcome, some of which can or could apply in any event. For example, the Agreement confirms the position of EU citizens and UK citizens in Europe. We should all welcome that.

It will significantly reduce the financial contributions that the UK makes to the EU. For those for whom that was an important consideration, that is also something to welcome.

It also contains welcome agreements over the UK’s sovereign base areas in Cyprus and a protocol on Gibraltar.

It does not, contrary to some commentary, provide a definitive end to freedom of movement: that will be considered in the next stage of the negotiations.

The Political Declaration, for its part, sets out an intention to explore co-operation on a wide range of areas, including participation in agencies such as the European Medicines Agency and the European Aviation Safety Agency.

All of this is positive, should be welcomed, and could be adopted in any event.

What the Withdrawal Agreement actually means - the drawbacks

There is a lot to cause grave concern, too.

Firstly, for the duration of the Transition Period and the Backstop, the UK will remain a rule-taker from the ECJ and under its jurisdiction in effect if not in name. The UK will retain all EU laws during the transition.

Under Article 4(1) - (2), the ECJ remains supreme, including the direct effect of EU law, and disapplication of Acts of Parliament that conflict. This would last throughout the Transition Period (always assuming that the Backstop does not come into effect) and, in the case of EU citizens’ rights and Northern Ireland, beyond.

So, the jurisdiction of the ECJ will not end in such circumstances: Article 4 requires the UK to give direct effect to ECJ rulings and continues its supremacy over Parliament - long one of the most troubling aspects of EU membership. This will clearly apply during the Transition Period - and throughout most of the “Backstop” provisions too, for as long as that is in force - potentially, as we shall see, indefinitely.

The ECJ is left with enormous powers of interpretation over the Withdrawal Agreement, including over all aspects of retained EU law (Article 174,) the financial settlement (Article 160,) and on cases arising during the transition (Article 87.)

Then there is the arbitration procedure envisaged, which Article 174 converts from a conventional international arbitration procedure (where you have judges from each side and then an independent one, handing down binding rulings,) to a wholly one-sided one whereby the question of whether the UK has correctly applied EU rules that it is expected to mirror is to be decided entirely by the ECJ - as is the case with the former Soviet republics of Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia.

The recently retired President of the EFTA Court, Dr Carl Baudenbacher, had this to say about this clause:

“This is not a real arbitration tribunal - behind it the ECJ decides everything. This is taken from the Ukraine agreement. It is absolutely unbelievable that a country like the UK, which was the first country to accept independent courts, would subject itself to this.”

So to sum up, not only would the UK continue to apply EU rules without any say in their making, but in the event of a dispute, the EU’s Court, not ours or an independent one, will make a binding decision.

Remember, if we were unable to agree a future trade relationship with the EU and were to enter the Backstop, much of this position may continue indefinitely. So let’s look at those important points now:

Would we be able to agree a future agreement, and if so, what would it be?

If we failed and had to enter the Backstop, how would we get out of it?

But this is a temporary agreement, isn’t it, so does it really matter?

As can be seen, there are very many aspects of the Transition Period part of the Withdrawal Agreement that are pretty difficult to welcome and I have only touched on a few of them above.

This is because this was always likely to be the case, given that the Government accepted long ago, for the purposes of providing business with some certainty, that there would be a “Transition Period” of around two years, whereby Britain remained subject to exactly the same EU rules and obligations as we do now, but without being a member.

To put it plainly, what I have outlined above is clearly deeply problematic - but does any of this technical stuff really matter in the long run or can we just take a pragmatic approach, lump these unpleasant provisions for now, and move on? This is the approach the Government is asking MPs to take, urging us not to ‘let the perfect be the enemy of the good.’

This argument only carries weight if the period of unpleasantness truly sets us on a clear path to a more acceptable future relationship or whether, if this future relationship shows no signs of materialising, the UK has a clear ability to exit the arrangements and what the effect would be on Northern Ireland if that were to take place.

The “Future Relationship” - and will we get there?

The Government will argue, relying on Article 184 of the Withdrawal Agreement and Article 2 of the Northern Ireland protocol, that the EU and UK are legally bound to work with “best endeavours, in good faith” to get the Future Relationship in place by the end of the Transition Period. But this is not a positive point. Rather it illustrates that there is no legal obligation to actually conclude a subsequent agreement: an obligation to negotiate is not the same as an obligation to reach an agreement (this is made clear by the Bolivia v Chile judgement, para 85 in footnote 11, page 25 of the Government’s Legal Position Paper.)

This is an important point. The Government sets great store by this, and describes it as a “high legal bar.” It is not, because it is barely what lawyers call “justiciable.” In other words, it is possibly incapable of being tried in a Court. How do you sue someone for not using “best endeavours”? If we try it, the EU will simply list a number of reasons that they say are genuine points of dispute, and how does the UK prove that they are not but the EU is acting in bad faith? We cannot.

In practice, how realistic is it going to be to seek to demonstrate that the EU is acting in good faith if it negotiates and demands terms on, say fishing or Gibraltar - both sabres that have been rattled - which simply are unacceptable to the UK?

All this would achieve is to involve the UK in years of expensive litigation debating “how good is “best”?” And it was made clear in the Government’s legal position paper (para 77) that during the Transition Period, it will be up to the ECJ to rule on whether the threshold of “good faith” and “best endeavours” have been met. This matters hugely because it is utterly one-sided: the plan is to have the Future Relationship agreed during the Transition Period, which could last for four years (if it is extended.) Thus, it would be the ECJ that could end up deciding when and if Britain is allowed to have an independent trade policy, or whether the whole country would enter an indefinite customs union.

Further, all 27 EU states have to sign off on the new Future Relationship. What if, say, Wallonia decides - as they did with CETA - to refuse to ratify the Future Relationship even only temporarily? The UK has no recourse to law, and hurtles towards the Backstop, all the time under more pressure and with the EU able to extract ever more concessions in any one of the wide amount of areas laid out in the Political Declaration.

Far more likely is that Spain will use this as a threat to draw further concessions with regard to Gibraltar or, as President Macron recently suggested, that the French would do so for more favourable access to our fishing waters.

And what will this Future Relationship be in any event? This is supposedly laid out in the Political Declaration. The difficulty is that this is extremely vague and promises nothing specific. It refers to a “spectrum” of possibilities and is written in aspirational, rather than definite, language. It is not a blueprint for a future deal, and covers anything from a Customs Union, to Chequers, to a Canada-style free-trade agreement - and everything in between.

Most seriously, it commits the EU to nothing - and has no legal force in any event. But if this deal is signed and has taken treaty form, it will be legally binding. We will have surrendered £39bn without the guarantee of any further relationship at all - let alone an acceptable one - beyond the flimsy 29-page outline that we have here.

The Withdrawal Agreement therefore represents the surrendering of Britain’s strongest cards - our money and, through the Transition Period and Backstop, access to our market - without any guarantee of what we are getting in return. Why would the EU be inclined to be helpful towards us in the face of such a weak, inept negotiating stance?

So there is every reason to think that it will be very difficult, if not impossible, to agree a favourable future trade relationship with the EU - because the Withdrawal Agreement stacks the deck in the EU’s favour. Further, we have no real idea of what that future agreement might be, meaning that further concessions can be expected.

Crucially, under the terms of this Withdrawal Agreement, business has no more certainty in any event because we will continue wrangling over the terms of Brexit for the next two years - and possibly beyond.

The “Backstop” - and can we get out?

It is around this issue that the criticism of the Government’s deal has now crystallised: assuming no future relationship is agreed and we enter into the Backstop, can we get out of it, and what would the effect on the Union be?

Were the UK to enter the backstop, the entire UK, including Northern Ireland, would enter into a customs union - for that is what it is - with the EU.

What is quite remarkable is that there is no break clause. Every international commercial agreement includes a provision where one party can leave by giving notice. Even the European Union - much more than just a commercial agreement - has Article 50, and even the Moldova Association Agreement has Article 460.

By contrast, this Backstop customs union can only be ended by mutual agreement, under Article 20 of the Protocol:

“If at any time after the end of the Transition Period the Union or the United Kingdom considers that the Protocol is, in whole or in part, no longer necessary to achieve the objectives set out in Article 1 (3) and should cease to apply”

“the Joint Committee shall meet at ministerial level to consider the notification…”

“If…the Union and the United Kingdom decide jointly within the Joint Committee that the protocol, in whole or in part, is no longer necessary to achieve its objectives, the Protocol shall cease to apply…”

The objectives in Article 1(3) are:

“This Protocol sets out arrangements necessary to address the unique circumstances on the island of Ireland, maintain the necessary conditions for continued North-South cooperation, avoid a hard border and protect the 1998 Agreement in all its dimensions.”

The underlining emphasis is mine, because they contain the essence of the matter, which is that the EU essentially has a veto on the UK leaving the “Backstop” because it has to agree that it is no longer necessary. There is no independent or unilateral mechanism to allow the UK to leave. I am not aware of any historical precedent where a democratic nation has voluntarily signed up to such an agreement.

And why should the EU come to the conclusion that the Protocol is no longer necessary? It would have the UK precisely where it wants it: a full, non-voting member of a customs union, collecting tariffs and paying 80% of them to the Commission, having surrendered control of its trade policy - no trade deals around the World - being required to offer access to its markets to the EU’s future trade partners but without reciprocal access in return. This would keep the UK as a captive market for the EU, required to follow its external trade policy, and existing to enable the EU to sell their huge £95bn a year goods surplus into the UK, without external competition, and without the UK able to lower food prices to their World, as opposed to EU, prices. The EU has happily kept Turkey in this position for decades.

Further, there are “level-playing field” provisions (Articles 10-12) in the protocol on the environment, state aid, workplace rights and other areas, all of which are designed to suppress the competitiveness of British industry by ensuring that the UK cannot derogate from the EU - in any way - to improve its competitiveness by shedding unnecessary and burdensome EU regulations.

It is not a particularly complicated proposition to suggest that if you concede these in a “temporary” Backstop that you are unable to leave without asking the other side’s permission, then you are not going to get better terms in a subsequent agreement, and you are not going to be able to leave. It is therefore naive to say that we do not need to worry about the Backstop because no-one intends to use it, because it is likely to become the baseline for any future trading relationship.

International relations are a hard, cold, merciless business where interests trump sentiment. History tells us that it is highly unwise for any sovereign country, still less a proud, ancient, stable and prosperous one with a long tradition of political freedom and self-governing democracy, to put itself in the position of hoping that a foreign power will treat it in the way that it desires for no other reason than goodwill.

The Government will argue that the Backstop is not intended to come into force, provided a long-term trade agreement is negotiated before December 2020. But the very existence of the Backstop as an effectively permanent “fall back” would, as I have explained, militate against the negotiating of such an agreement in the first place.

It is true that Article 1(4) says that the Backstop is “intended to apply temporarily.” But I cannot help but feel that this is inserted simply to make us feel better, given that the provisions that govern how the protocol can be replaced give the EU a veto, as I have explained above.

A further Government argument is that Article 50 is not intended to be used to establish a permanent relationship, that this a strong part of the EU’s legal architecture which they will not derogate from. The objection to this point is simple: if the Backstop is valid as part of the Withdrawal Agreement because it is nominally temporary, if indeterminate, it will not become invalid simply because it runs on and on. We can see that Article 50 has no time limit, as demonstrated by citizens’ rights, which last for their lifetimes. Put another way, as long as the Backstop is never called “permanent”, there is nothing to stop it from simply being indefinite.

I put this point directly to the Attorney General in the House of Commons and his response did little to assuage my concerns.

The Attorney General was, however, refreshingly candid in his statement. He confessed to having wrestled with the question of whether to support the Agreement and noted:

“As my right hon. Friend knows, the job of any lawyer for any client is generally to assist the client to make decisions as to the balance of risk in any decision that they are about to take. There is no question but that the absence of a right of termination of the backstop presents a legal risk. The question of whether it is one this House should take is a matter of political and policy judgment that each one of us must grapple with. The House has heard and, for reasons that I am not going here to expatiate upon, I have taken the view that compared with the other courses available to the House, this one is a reasonable, calculated risk to take. Other Members of this House must weigh it up, but that is my view.”

There is therefore no question of the UK having a legal right to exit the Backstop. It is rather a political question as to whether one is prepared to take the risk of locking their country into an arrangement - quite possibly in perpetuity - which is so profoundly detrimental to its political, social and economic well-being.

The problem with the Backstop in any event because of the negotiations going forward

So let us now address another of the Government’s points: that the EU does not want us in the Backstop for any longer than is necessary because it is uncomfortable for them too.

Firstly, as I have explained above, the EU would have the UK in a position of a captive market, and that would seem to me to suit them very well indeed.

Secondly, this is beside the point. Even if the EU does want us out of the Backstop as soon as possible, the fact that we will have put ourselves in such a weak negotiating position will mean that they will be able to extract maximum pressure, and maximum concessions from us before that new agreement is signed: fishing, freedom of movement, regulatory alignment, payments into the budget.

That would put the EU in the best possible negotiating position and would offer it absolutely no incentive to negotiate a future trade deal, and certainly not on terms more favourable than those that exist now. It will be able simply to sit on the existing terms, and refuse to agree to any that are better for the UK than those under the WA, knowing that the UK will have to continue to stay in the Backstop if they do not agree.

In any event, it appears that the Withdrawal Agreement, rather than simply being a “bridge” to a future trade deal - be it Chequers or Super Canada or something else - is in fact to be built upon. The Political Declaration states (para 23) that our future relationship will “build on the single customs territory provided for in the Withdrawal Agreement.”

Although the Prime Minister insists that we are leaving the customs union, it is difficult to read the Withdrawal Agreement and believe that we will be doing so in anything but name, regardless of whether the Backstop arrangement kicks in. The EU could conceivably request that a future trade agreement has to replicate the effects of the Backstop in full to avoid its activation, making membership of the customs union – or a hybrid equivalent –inevitable.

This was in fact a late addition to the Political Declaration, and one which ultimately led former Brexit Secretary Dominic Raab to tender his resignation.

And why take my word for it? What about Sabine Weyand, Michel Barnier’s deputy, who has been the subject of multiple reports, picked up by The Times, that the EU intends to use the Backstop as the basis for the Future Relationship, with the UK locked into the customs union and “level playing field” arrangements (PD para 17) on an ongoing basis:

“We should be in the best negotiation position for the Future Relationship. This requires the customs union as the basis of the Future Relationship… They must align their rules but the EU will retain all the controls. They apply the same rules. UK wants a lot more from Future Relationship, so EU retains its leverage.”

And we need only look at the French comments on fisheries, the Spanish attitude to Gibraltar, to see the sort of concessions that we are going to be asked to make to obtain a trade deal in the future. And look at former Science Minister Sam Gyimah’s observations on how the EU changed the rules over the Galileo satellite system in order to damage the UK to see how hard a line the EU is going to take, why the lie is given to “best endeavours” and why it is critical that Britain is not at their mercy in the negotiations that lie ahead:

“Having surrendered our voice, our vote and our veto, we will have to rely on the ‘best endeavours’ of the EU to strike a final agreement that works in our national interest. As Minister with the responsibility for space technology I have seen first-hand the EU stack the deck against us time and time again, even while the ink was drying on the transition deal. Galileo is a clarion call that it will be ‘EU first’, and to think otherwise – whether you are a leaver or remainer - is at best incredibly naïve.”

This is a good time to remind ourselves of the fact that the Withdrawal Agreement is a legally binding treaty, whereas the Political Declaration is only aspirational and has no legal force. The EU is not required to come to an agreement on a Future Relationship.

The Government’s former chief Brexit negotiator, Sir Ivan Rogers has recently made some points on the EU’s approach to the talks: its aim has been to “maximise leverage during the withdrawal process and tee up a trade negotiation after our exit where the clock and the cliff edge can again be used to maximise concessions from London. So that they have the UK against the wall again in 2020.”

Further, he predicted where we would be in two years time:

“First, we shall be having precisely the same debate over sovereignty/control versus market access as we are now. The private sector will still be yearning for clarity on where we are going, and not getting much.”

“Second, it will be obvious by early autumn 2020 that the deal will not be ready by the year end, and that an extension is needed to crack the really tough issues,” he said. The EU is in no rush. “It sits rather comfortably with the UK in its status quo transition, with all the obligations of membership and none of the rights, and will use the prospective cliff edge to force concessions.”

“Third, the Irish backstop, enshrined in the Withdrawal Treaty will still be in place.”

None of this insight suggests that it would be wise to accept this deal.

So what is a customs union, and why is being part of one so undesirable?

Surely one is necessary in order to solve the Northern Irish border question?

Firstly, what is a customs union?

I know this sounds technical, but it is absolutely critical to understanding this issue. A free-trade area is a group of states which have removed all - or most - tariffs and quotas on trade between them, be that on all trade including services, or just manufactured goods. Free movement of labour - but not of people - may or may not be included. Examples of free trade areas are EFTA (Norway, Switzerland, Iceland and Lichtenstein,) and NAFTA (United States, Canada, Mexico.)

A customs union, on the other hand, not only involves the abolition of tariffs and quotas as above, but also includes a common external tariff. Because of this, its members give up their independent trade policy, which is conducted by the block as a whole. They cannot sign trade agreements, they cannot set their own tariffs or quotas. Because trade is the lifeblood of any country, being a member of a customs union is a major loss of sovereignty and independence for any state. They will often only exist where one state administers another, or where a tiny state outsources its trade policy to larger neighbour: Swaziland and Lesotho, for example.

The EU is a customs union, not a free trade area. The other major ones are Mercosaur and the Andean Community, both of which were created when the EU made clear that it would not sign a worthwhile trade treaty with individual countries, only with a major bloc.

The best way to understand it is this: Britain could join NAFTA, which is a free trade area, at the same time as making a trade deal with the EU. But Britain, as a member of the EU, could not join NAFTA, because the EU insists on exclusivity.

So what does this mean? Economists would generally prefer free trade areas, because they facilitate global trade without the politics. And because of modern customs check processes, customs unions are no longer necessary anyway: they are a nineteenth century relic.

Customs unions, by contrast, are preferred if your goal is to encourage political union.

Remaining in a customs union without being a member of that body really is the worst of all worlds. You have no say over the level of tariffs that are charged, you have no independent external trade policy (i.e. no freedom to sign trade deals with other countries,) and if the EU manages to sign a free trade deal with another country or block, that country has access to the UK’s markets on those terms, but the UK does not have reciprocal access.

Remember that the UK has a huge trade surplus with the EU in goods, meaning that they sell much more to us than we do to them. So there are clear motivations for them to keep the UK in a customs union, which gives their exporters preferential access to our huge market - the fifth biggest economy in the World - whilst allowing Brussels negotiators to use that same market as a carrot to attract better terms for the EU that will not be enjoyed by Britain. It would essentially mean that the UK market – one of the most dynamic in the world - would be reduced to a captive market to be used for the benefit of the EU.

It would negate many of the advantages of Brexit, and we would have paid £39bn for the privilege.

So be absolutely clear: a customs union is a political device, intended to bring together separate states in an effective or express political union.

With that stated, it is crucial to understand that the Northern Irish border is a matter that has been shamelessly weaponised by the European Commission as a means of dictating the shape of the talks. The Backstop arrangements which, as we have already established, stacks the next round of negotiations wholly in the EU’s favour, only exist as a means of preventing a hard border on the island of Ireland. A hard border which, it must be noted, is desired by neither the UK, the EU or the Republic of Ireland; a hard border which the leaders of the UK, EU & Republic of Ireland have all refused to erect under any circumstances; and a hard border which the Chief Executive of HMRC, his Irish counterpart, and the WTO have all said is wholly unnecessary even in the event of a ‘no deal’ outcome. Existing checks and procedures can manage this process technically – but these proposals do have to be engaged with.

The “Backstop” - what is the effect upon Northern Ireland - and on the Union?

Then there is the fact that Northern Ireland is treated separately from the rest of the UK: a border down the Irish Sea, keeping Northern Ireland in the whole Union Customs Code as well as the huge range of EU single market rules that are applied over some seventy pages in Annex 5 of the Protocol.

Northern Ireland is therefore forced to accept regulatory alignment even if Great Britain does not. UK goods moving to Northern Ireland will require checks: see Article 7 of the Backstop which only guarantees trade from Northern Ireland to Great Britain, not the other way around.

That really is against the principles of the Good Friday agreement, far more than any technical border checks could ever be, as well as, it seems to me, against the Articles of Union of 1800. That makes these provisions a threat to the union, for Scottish Nationalists will now demand the same differentiation.

The effect of this is that if the UK were ever to find a way of leaving the Backstop, it would have to leave Northern Ireland behind. Dominic Raab, on his resignation as Brexit Secretary, reported Martin Selmayr, Secretary-General of the European Commission, as having said that Britain must pay a price for leaving the EU, and that price is Northern Ireland. Whether that chilling desire is true or not is perhaps beside the point: that is the effect of this deal.

Any other considerations: should the Withdrawal Agreement be supported in any event?

We can therefore dispense with the fiction that this is a “good deal.” It is not. But are there other good reasons to support it nonetheless?

Might those include, for example:

To support the Prime Minister out of party/personal loyalty?

In the national interest?

Because it is a compromise?

Because business needs certainty, it is in the country’s economic interests, to avoid “chaos” or “no deal”?

Because it is all that is on offer?

Because not supporting it risks a Corbyn Government or a Second Referendum?

Because my constituents are tired of hearing about Brexit and want us to talk about domestic priorities?

To support the Prime Minister, or out of party loyalty?

This is a powerful argument, particularly for someone who places great importance on loyalty and dislikes the fickle self-interest which often prevails in Westminster. I should also say that I have the utmost admiration for the Prime Minister’s determination and tenacity in negotiating a deal which she no doubt sincerely believes to be in the national interest.

But with that said, my highest loyalty is owed to my country and my constituents, and if this conflicts with my loyalty to my Party then I am afraid country and constituents have to triumph every time. Admiring someone is no reason for supporting a course of action that you believe to be wrong. The fact that ultra-loyalists as Mark Harper and Andrew Mitchell have come to the conclusion that they cannot support the Government’s line is a clear indication that something is badly wrong.

I recognise the immense privilege and responsibility that comes along with being a Member of Parliament, and that I am sent here by the people of West Oxfordshire to serve my country and constituency, in that order. Party comes a distant third and self nowhere at all.

Furthermore, it is the duty of every member of Parliament to scrutinise the Executive and hold it to account. There is little use in Parliament if all MPs do is obediently follow the instructions of the Whips. Far from looking out for our constituents, we are in fact doing them a disservice if we fail to raise objections when and where we see them.

And on this most momentous of moments, there is simply not a question of holding one’s nose and voting something through just to be a ‘team player’ or out of fear for upsetting persons of influence. There is far too much at stake.

In the national interest?

Of course everyone wants to act in the national interest. But that does require some analysis of what the national interest actually is. I struggle with the proposition that the national interest is served by making the country subject, potentially in perpetuity, to rules set outside this country over which we will have no say, simply because that will get a deal through, as opposed to trying again.

Because it is a compromise?

Like the vast majority of people, I want to see a deal with our closest trading partners, and naturally that will involve a compromise. But that cannot logically mean a deal at any price, and everyone must realise that there is a point when compromise tips over into capitulation. For me, that comes when we are asked to sacrifice fundamental democratic accountability. Being prepared to read the agreement and decide where that point lies does not make me a “Brextremist”, a “hard-liner” or a “purist.” It just makes me someone who is prepared to do his job properly.

I am quite prepared to accept compromise in a whole range of areas, but I cannot support a deal that will leave us in many ways with less control and less democratic accountability than we have now.

Because business needs certainty, it is in the country’s economic interests, to avoid “chaos” or “no deal”?

There is no doubt that economic interests - people’s jobs and the success of businesses - are the most powerful reason to consider voting for any deal.

But this would only offer a temporary economic benefit, and because of the ongoing nature of this deal - where we have not even tackled the future relationship yet - there is little more certainty by following this deal than there is without it.

Firstly, because the nature of the Transition Period will mean that we are subjected to years more of excruciating debate and uncertainty - not the reverse. This is not certainty. Businesses have no greater idea now of what the Future Relationship will be that they do now, and will be condemned to years more wrangling, given that the EU has absolutely no incentive to agree a future trade relationship early, given the huge leverage that will be given to them, the closer we get to the Backstop.

Secondly, because giving the EU the keys to our economy without representation is simply an invitation for regulations to be passed that suit them, and not us. When those economic effects are felt, under this deal, Parliament will be powerless to do anything about it. And there will, undoubtedly, then be irrevocable economic ill-effects.

As one of my constituent companies put it to me only recently, “Nobody has ever bought from us because we were members of the EU. People have bought from us because we were better than the competition….”

It is my job to ensure that they continue to have the economic freedom to be a success, and that Parliament has the freedom to legislate if that is not the case.

Thirdly, there is no reason why there should be “chaos” - because there are alternatives.

Because it is all that is on offer?

The argument that “it is all that is on offer” is not only unappealing per se, but it is simply not true. The substandard nature of this deal might be one that could be swallowed, with distaste, were it not for the fact that alternatives are available.

“So, what’s your plan?” is an entirely reasonable question to ask. Well, the flavour of alternative you prefer will depend upon your tastes. The first and obvious answer is that the Prime Minister return to Brussels and make clear that this deal is one that will not pass the House of Commons, and that there have to be changes, using whatever negotiating points are available. The inclusion of a unilateral exit mechanism to the backstop, or indeed its removal altogether, would be a very good place to start, and may give us an acceptable Withdrawal Agreement that will enable us to move towards a settled Future Relationship.

I have also long thought that British membership of EFTA should be seriously considered, favouring, in those circumstances, a Switzerland-style relationship with the EU through a system of bilateral agreements. I have even given - and continue to give –British membership of the European Economic Area (EEA) through the EFTA pillar, some serious thought.

The EEA/EFTA option amounts to ongoing membership of the single market, and would be closer to the common market which people thought they were joining in 1975 and which the vast majority of British people are supportive of. There are many drawbacks to this option, which I would not favour over a Canada +++ free trade deal model, but in the interests of compromise, and recognising the close nature of the referendum result, I am prepared to give it serious thought.

Some colleagues have, however, been pushing for a ‘Norway-plus’ model, which adds an unnecessary customs union to the EFTA/EEA model and which would simply reintroduce all the objections that I refer to above, and which are the primary objections to the Prime Minister’s deal.

One of the primary benefits of the EFTA/EEA model is that we would regain complete control of our external trade policy, so it seems bizarre that many appear to wish to voluntarily surrender this.

In any event, we can see that there are options that may offer us a way forward that breaks the Parliamentary deadlock and ensures the backstop is never initiated.

But what about the Northern Irish border? Isn’t a customs union Backstop necessary to solve that problem?

I recognise that this is a sensitive political issue, but it is not a practical one. As I have explained above, a customs union is not required in order to see continued free-flow of trade across the border, which can be managed using existing technical processes. The Government’s insistence on there being a Backstop is therefore something of a mystery.

The British Government and HMRC have said multiple times that even in the event of “no deal”, a physical border would not be built on the UK side of the Irish border. At a recent liaison committee, Dr Julian Lewis MP repeatedly asked the Prime Minister for any imaginable circumstances in which such a border would be created - without answer. The Irish equivalent of HMRC, even the Irish Taoiseach (Prime Minister,) Leo Varadkar, have said that in the event of no deal, no “hard border” would be built on the Irish side either.

Last week, the World Trade Organisation said that it would not demand a physical border, or even call for additional checks.

Numerous customs experts, both British and European, have argued that tariff differences between Northern Ireland and the Republic could be handled without intrusive border infrastructure.

Would the EU send its own officials to conduct checks against the wishes of the Republic of Ireland? No - even the EU have conceded the point! What they long derided as “magical thinking” - the use of existing technical solutions that deal with the existing VAT, currency, excise border - is now accepted as part of the Withdrawal Agreement (see the Northern Ireland Protocol, Articles 6-8) - save that they want the border down the Irish Sea, instead of across the land border.

What is in any event quite clear that the need for some new, elaborate solution to an exaggerated Irish border problem has been the tail that has wagged the dog of these negotiations. It should not have been wagging at all - and does not need to now. There is simply no need for new infrastructure at the Irish border and trade and people can still flow freely.

Because not supporting it risks a Corbyn Government or a Second Referendum?

On the contrary. The DUP, on which the Government depends for its working majority, have already indicated that they will reconsider the confidence and supply agreement if this deal is passed by the House of Commons, have abstained in some Finance Bill matters already to make that threat crystal clear, and the Government’s loss of the votes holding it to be in contempt of Parliament were due to the loss of the DUP.

So, passing this deal makes the collapse of the confidence and supply agreement and the fall of the Government much more likely. Indeed, the only hope of preserving this government is to vote against this deal.

As to a second referendum: this is not as straightforward as its campaigners like to claim, requiring the Government to introduce legislation that would be bitterly fought through the House of Commons - and take approximately a year to conclude.

I do not subscribe to the view that we should accept this deal out of fear that not doing so jeopardises Brexit itself. When 17.4 million people voted to the Leave the European Union in June 2016 – against the might of the UK political establishment – they did so not just so that we could get our withdrawal over the line and be able to say that ‘we are no longer members of the EU” but rather because they wanted to see a fundamental change in the way the country is governed.

Because our constituents are tired of hearing about Brexit and want us to talk about domestic priorities?

Certainly that is a frequently expressed view.

However, it is practically unheard of in modern international relations for an independent state to put itself under foreign jurisdiction and to prevent its citizens from having even an indirect role in deciding the laws that govern them. It is equally unheard of for a commercial arrangement not to have an exit clause that can be triggered unilaterally on giving notice (and the civil service appear to have been aware of this and prepared a negotiating text to deal with it, if you believe The Times’ splash.)

If MPs were to put the UK in that position, this might get us through the next few weeks, but it certainly will not get us through the next few years: when the public start going to see their MPs and are told that there is nothing to be done about a particular regulation because it is in the EU’s control, the public will expect their MPs to have understood what they were signing up to at the time, not to merely sign up to any deal, no matter how terrible, simply to get the whole thing over and done with.

Agreeing to something that you do not like simply in order to stop talking about it is not a sensible way to run a life, never mind a country. The concessions made in this agreement will come back to haunt us if we agree to them. It is up to us all to find a better way.

Conclusion

So the position is as follows.

Assume Parliament passes the proposed withdrawal deal. Then assume that the EU continues to resist the UK’s trade proposals during the 21-month “implementation period”. Under those circumstances, we would enter the Backstop and the UK would have paid most of the £39 billion exit bill.

In addition, the UK would be in a customs union, without an independent trade policy, under the power of the ECJ and without any influence in Brussels. The only way out of that open-ended, subordinate status is to sign up to something that is agreeable to the EU.

So the issue comes down to one of trust: can we trust the EU to be nice to us? Or is it more likely that the EU will maximise its own negotiating position, and drive an impossibly hard bargain to obtain a deal that suits itself? Surely it is naive to allow ourselves to be put into that position.

And let us re-state the basic principle. The UK is legally and morally entitled to withdraw from a European project with which she has never been comfortable and which is clearly evolving in a federally-integrated direction that British voters do not wish – and never will wish - to go. There is no reason to be ashamed about wishing to restore democratic self-government, or to be apprehensive about rejecting a system that those on left and right have long criticised for having a “democratic deficit”, that cannot be removed by voters, even when it persists in errors.

Those who voted for Brexit did so because they wanted a freer, more democratic, more global Britain, one that governed itself. This does not mean - and they did not want - to sever all links with our European friends and allies. We simply wanted to be able to stand back whilst they pursued their long-held goal of political amalgamation.

The deal that the Prime Minister has negotiated does not offer that, rather it offers a future Britain that is in almost every way as constrained as now, without a way out, and with no way of exploiting the commercial opportunities that Brexit offers.

So with all that analysis laid out, I do not see how, in its current form, the Withdrawal Agreement achieves the ends I have laid out, and I struggle to see how anyone, whether they voted leave or remain, would want me to support it.

Robert Courts MP